Echoes of the Rumble: Contextualising a historic moment that continues to resonate

Authors -

Shubham Jain

Boxing, a sport deeply entrenched in physical combat, often finds itself at the crossroads of ethics, morality, human rights and societal perceptions. This haunting assertion from Ralph Ellison offers a profound lens through which to view boxing's intricate dance with identity and visibility.

“I am an invisible man. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Boxers often grapple with invisibility. Their palpable physicality in the ring is juxtaposed with societal blindness to their narratives, struggles, and individuality. Historically, many fighters, especially those from marginalised backgrounds, have become mere tools in a more extensive system, their essence reduced to a spectacle for the masses. This systematic erasure resonates with the very heart of Ellison's work: the struggle for individual recognition in the face of overwhelming societal prejudice.

This dance of visibility and invisibility became even more pronounced during one of boxing’s most iconic moments, the World Heavyweight Championship in 1974. It was contested between former champion Muhammad Ali, and the then undefeated reigning champion, George Foreman. Earlier in 1974, Ali had defeated Joe Frazier for the right to take on Foreman for the Championship. The fight took place forty-nine years ago today - on 30 October 1974 in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). However, it was much more than a boxing match. Ali referred to the fight as the “Rumble in the Jungle”— and the name stuck. The Rumble transcended the world of sports, carrying profound historical, social, political, human rights, and cultural significance, both locally and internationally.

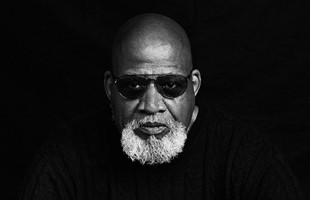

The Centre for Sport and Human Rights (CSHR) in partnership with the theatre company Rematch is hosting a special one-off performance of "Rumble in the Jungle Rematch" on 31 October 2023. Rematch re-imagines history’s greatest sporting moments as incredible immersive events. With this special event CSHR has the opportunity to bring together the sport and human rights community in London to connect with each other, and also pay tribute to the human rights legacy of Muhammad Ali. This is also a fitting and appropriate moment for the announcement of Dr. Harry Edwards as a new Patron of CSHR.

The Rumble was a spectacular showcase of the Black diaspora - a contest between two Black men, promoted by a Black man (the infamous Don King) in a newly independent African country. Events built around the fight included, ‘Zaire 74’, a three-night-long music festival featuring some of America and Africa’s top Black musical talent including James Brown, BB King, The Spinners, Miriam Makeba and Zaïko Langa Langa. This made the fight even more memorable as a diasporic and pan-African cultural affair.

However, the fight was not without its shadows. The bout was as much a political spectacle as a sports event. During the 1960s and 70s, a growing number of African countries were gaining independence from their colonisers. Sport was often seen as a means to unify newly independent nations and people. From 1885 until independence in 1960, the local population in Congo faced widespread atrocities and systemic resource drain under Belgian colonial rule. Against the backdrop of the colonial destruction and Cold War geopolitics, power in Congo was seized by military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko in 1965 from the democratically elected, left-wing independence leader Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba.

The Rumble was promoted as symbolising Africa's emergence as a significant player in the world of sports, entertainment and politics, a battle for African pride and recognition. Mobutu promoted it as a symbol of African unity and progress, agreeing to pay each boxer $5 million for participating, to draw the world's attention to his country, and to deflect attention from his authoritarian regime, human rights abuses and the political and economic challenges faced by the nation. It is likely that Ali and Foreman were aware of Mobutu’s tactic of using the fight as a means of putting his country on the map. However, neither boxer made a comment about Mobutu’s despotism. In many senses, the conflicting and contested dimensions of the Rumble represent the same characteristics we continue to see with the hosting of mega-sporting events as displays of soft power, political positioning, alliance building and nation branding. Indeed, the idea that sporting spectacles can detract or distract from socio-political realities and human rights abuses is now a well trodden road.

The Rumble was also very much a product of its particular time. Ali and Foreman served as proxies for distinct political thoughts. Arguably, both boxers became pawns in a giant geopolitical game, their identities and images potentially co-opted for broader agendas.

Ali was a prominent and defiant figure in the civil rights movement and represented black nationalism and black power resistance. In the late 1960s, Ali had become somewhat of a “politically” invisible man. When Ali refused being inducted into the military during the Vietnam war in 1966, he was stripped of his passport, boxing titles and was unable to fight for almost four years. Despite his globally renowned status and reputation, Ali was sidelined by powerful institutions that refused to see or accept his anti-war beliefs. The Rumble was not just a fight for the heavyweight title but a symbolic assertion of Ali’s re-emergence into visibility.

Foreman, on the other hand, was considered an establishment and patriotic nationalist figure. At the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, when Tommie Smith and John Carlos staged the black power salute, Foreman celebrated his boxing gold medal with an American flag. Thus, while Ali was seen as an anti-imperialist and anti-racist figure, Foreman was perceived and portrayed (perhaps somewhat inaccurately) to reflect establishment values. Even in terms of their boxing prowess, Foreman, painted as an indomitable force, and sometimes reduced to a mere emblem of brute strength. In contrast, Ali was lauded for his strategy, especially his "rope-a-dope" tactic during the Rumble. Ali and Foreman became more than just boxers; they were symbols representing broader narratives and communities.These narratives, though compelling, risked stripping both fighters of their multifaceted personas.

Ali’s activism and political stances, particularly his anti-war advocacy helped him build a close connection with and gather support from local people in Kinshasa. Therefore, Ali’s performance against Foreman was seen as part of the struggle for everyone fighting against injustice, inequality and imperialism. His victory was seen as a triumph of the African-American and the African people and their values, and for postcolonial communities around the world. It inspired a generation of artists, activists and boxers. Kinshasa celebrated his victory for days. The Rumble was also a cultural milestone, with the phrase "Rumble in the Jungle" itself becoming a cultural reference for any major clash or confrontation.

While the Rumble was a significant sporting and cultural achievement, it left a contested legacy. Mobutu reaped massive personal profits from the event. His corruption and impoverishment of the country and its resources as well as the human rights abuses during his regime are well-documented. The stadium which served as a venue for the fight houses a boxing club named in Ali’s honour. However, there is little evidence to suggest that the Rumble left a transformational sporting legacy for Congo or Africa. Indeed securing a social legacy from major events continues to be a challenge in most locations, something that CSHR works on extensively, including through a new handbook on mega-sporting events and human rights.

The Rumble also epitomised the complexities of boxing, identity, and power. Ali and Foreman, through their roles in the event, navigated the murky waters of visibility and invisibility, battling not just each other but also the weight of history, politics, and societal expectations. In a world where athletes are often reduced to mere statistics or sensational headlines, it's essential to remember Ellison's poignant words. Behind the spectacle, behind the narratives, lie individuals of "flesh and bone, fiber and liquids" who, like all of us, seek to be truly seen.

Rumble in the Jungle Rematch is an opportunity to be immersed in this historical and socio-political background and reflect on the contested legacies of the Rumble.